J Krishnamurti – A Portrait

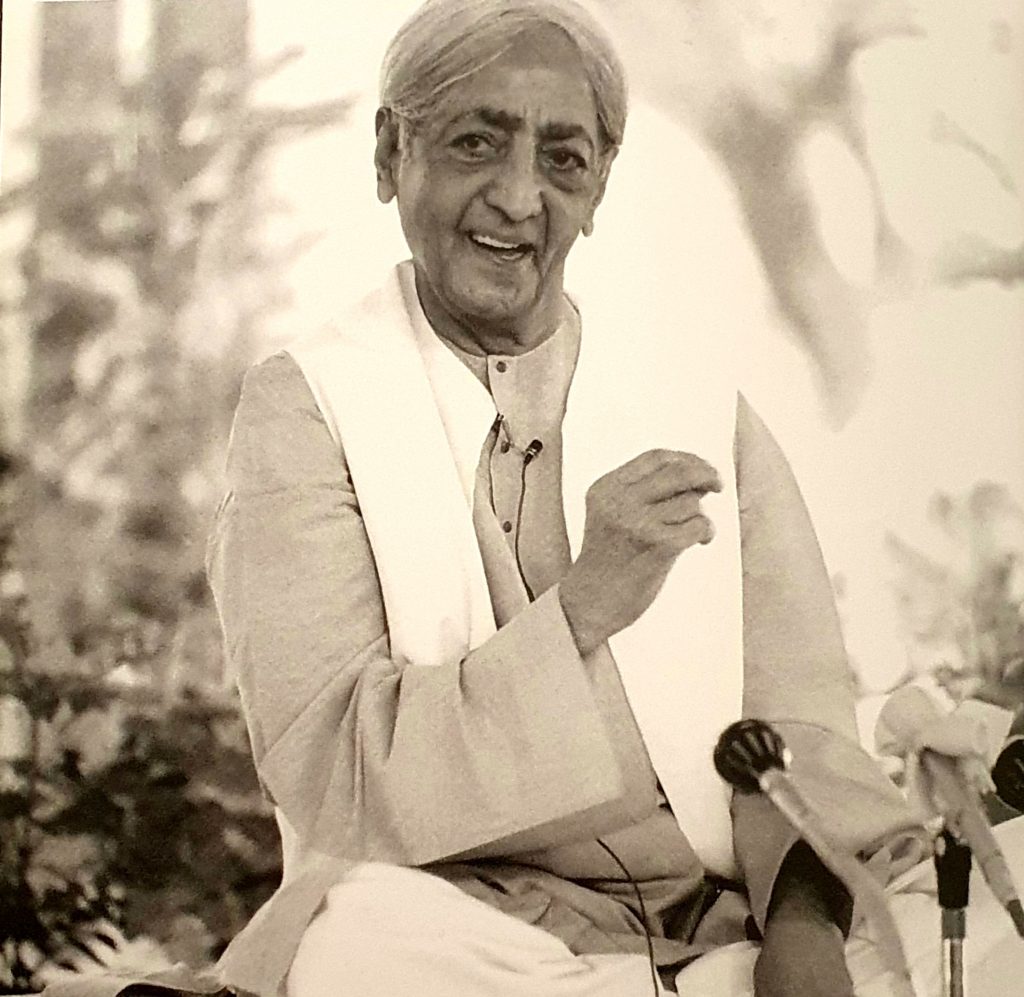

The life of J Krishnamurti, the philosopher-sage, was of the nature of myth. Young in mind, straight-backed with the majesty and beauty of an ancient Deodhar tree, he wandered around the world, teaching and healing the minds of the vast numbers of young and old, the intellectual and the simple human being, who came to him overburdened with conflict and sorrow.

Krishnamurti was born in Madanapalle, a small town in Andhra Pradesh, as the eighth child of a Telugu Brahmin government official. The signs of his mystical nature were evident in him from early childhood. His mother died when he was young. Though he was vague and uninterested in studies, often beaten at schools, his father had noticed an unusual capacity in the child for silence, observation and attention. He describes the boy Krishnamurti standing for hours watching the clouds form in the sky, looking at plants or sitting cross-legged observing the behaviour of ants. Narayanaiah, Krishnamurti’s father, was a Theosophist, and after retirement sought employment at the headquarters of the Society at Adyar.

One day when Krishnamurti was playing on the beach, he was noticed by C.W. Leadbeater, a clairvoyant and one of the top men in the Theosophical hierarchy. Leadbeater was struck by the luminous aura of the child,whom he found to be pure and free of all selfishness. The esoteric masters of the Society had instructed their disciples to be on the watch for a great Being who was to manifest in the world. Annie Besant took the child and his brother Nitya under her protection, and guardians were appointed to prepare the body of Krishnamurti for the coming of the great being.

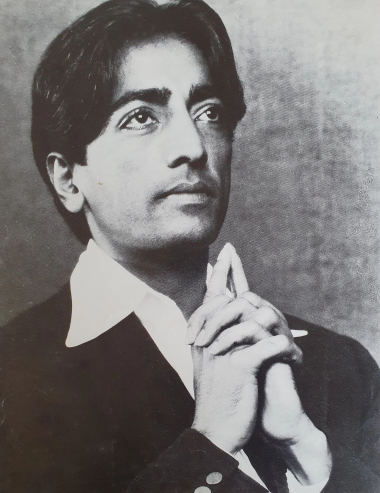

As a boy Krishnamurti had the supreme beauty of a forest fawn. The face was oval. The large, wide open eyes gazed into the distance. There was gravity and dignity. As he grew up, vast hierarchical organizations were built around him, and estates, lands and endowments were gifted to him for his work. Devotees from all over the world flocked to him. Adulated by vast numbers, arousing the cynical comments and derision of others for his role as the coming Messiah, he grew up as a sensitive, vulnerable young man with little to say.

The death of Nitya was Krishnamurti’s first contact with sorrow. It possibly triggered the awakening in him of that illumined intelligence which, while dormant, had sustained him through the years. He grew aware of the illusions and ambitions that made up his environment. He saw the pettiness of most of the so-called great ones. He saw that the structures and hierarchies that had been built in his name were seeking to imprison him.

Annie Besant whom he loved and respected was ageing. Large endowments of land money had created vested interests; conflicts were surfacing. At that time Krishnamurti was undergoing powerful mystical experiences. Though he rarely spoke of that period, everything that he had been taught or had come to accept was being negated. A new Krishnamurti was emerging, still shy, reticent but totally free.

In 1928, at a camp held in the 5,000-acre estate which had been gifted to him and which was the centre of the organizations set up in his name, Krishnamurti said ‘Truth is a pathless land. No organization, no belief can lead to truth’. The thousands of devotees who had gathered to hear him were bewildered. ‘I have no disciples – gurus step down the truth. Truth is within yourself.’ In one clean sweep he denied all hierarchies in the religious mind. The following year he dissolved the Order of the Star, the main organization built for the coming of the World Teacher. He gave back to the donors the moneys and vast properties, including the 5000-acre estate in Holland. In 1933, with the death of Annie Besant, his last links with the Theosophical Society snapped. Then, free of all property and organizations, alone except for a few friends who later were to rally round him, he left the Society, its hierarchical organizations, its rituals and beliefs.

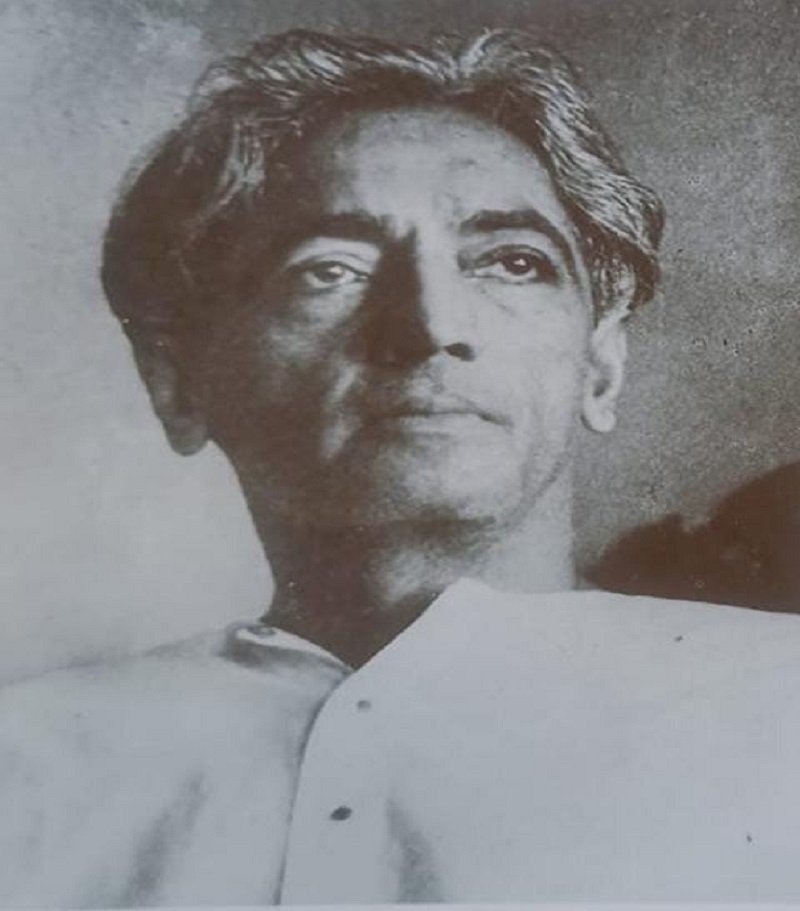

During the years of World War II he was stranded in Ojai, California. Much of the time he was alone,cultivating roses and milking cows. He was inwardly alive, listening, observing, probing, questioning the world within and around him. In the silence of his solitary walks, the teachings flowered. Aldous Huxley, who lived close by, became a friend. Huxley ,one of the most erudite minds of his times, talked; Krishnamurti listened. In turn, Huxley listened and learnt to be silent when Krishnamurti spoke of perception of time and of awareness. In 1961 just before his death Aldous was to hear Krishnamurti speak at Gstaad in Switzerland. Writing to a friend he described it as amongst the most impressive things; ’such authority, such uncompromising refusal to allow the home moyen sensual any escape or surrogates, any gurus, saviours, fuehrers, churches: I show you sorrow and the ending of sorrow.’

Drawn by Krishnamurti’s supreme presence, the beauty, stillness and compassion of his being and his capacity to heal the mind and unburden sorrow, the young and the man seeking God, the social worker and the politician came to him. In his public discourses, in his small discussion groups, in the individual interviews he gave, he negated all beliefs, all psychological and religious traditions, all gurus and crutches to reality. He probed into the human mind with the same extensive awareness as he gave to everything he did, from talking to a child to facing a mother whose son was dead. Questioned on his role, he said, ‘I am only acting as a mirror to your life,in which you can see your life as you are; then you can throw away the mirror; the mirror is not important.’ He spoke of self-knowing as the beginning of all wisdom. ‘Read every word, every phrase, read every paragraph of your mind – and you cannot read if you are condemning or justifying or if you are not awake to the implications of every thought.’ To the man in sorrow, with deep compassion he said: “The problem of sorrow ceases to exist not by transforming sorrow into happiness, greed into love, but in a transformation of the ground in which sorrow springs. The change or transformation is therefore not in quality but in nature, in dimension.’

Krishnamurti did not deny the wonder of science and technology. He was profoundly interested in the mechanical workings of the computer and the ever-receding limits to its functions. But seeing the inherent dangers in the present situation he demanded a mutation in the human mind so that the tool did not take over the inhuman role of master. For this the ‘within’ could no longer be ignored.

Krishnamurti held discussions into man’s problem with the great scientists of the world, men working at the frontiers of scientific knowledge, psychiatrists, thinkers, religious heads, political leaders, students and children. With the children in the many schools started to serve as a milieu for his teachings, his language became lucid, simple. He discussed with children their relationship to nature and to each other, fear, death, authority, competition, love, freedom. The child responded at first shyly, then with a spontaneous freedom. He asked the child to watch thought, in his mind, as he would watch a lizard moving across a wall, to watch every movement, not letting a single movement escape. He told the child that academic excellence was essential, but he also spoke of the awakening of intelligence which arose out of observation, self-knowing and compassion. Could these two streams be fused? He questioned. The child listened, questioned, perhaps understood more directly than the many who came with minds burdened with knowledge.

Krishnamurti held discussions into man’s problem with the great scientists of the world, men working at the frontiers of scientific knowledge, psychiatrists, thinkers, religious heads, political leaders, students and children. With the children in the many schools started to serve as a milieu for his teachings, his language became lucid, simple. He discussed with children their relationship to nature and to each other, fear, death, authority, competition, love, freedom. The child responded at first shyly, then with a spontaneous freedom. He asked the child to watch thought, in his mind, as he would watch a lizard moving across a wall, to watch every movement, not letting a single movement escape. He told the child that academic excellence was essential, but he also spoke of the awakening of intelligence which arose out of observation, self-knowing and compassion. Could these two streams be fused? He questioned. The child listened, questioned, perhaps understood more directly than the many who came with minds burdened with knowledge.

There is a tendency today to see Krishnamurti’s teachings as a soft teaching, love and freedom. In reality the teachings demand not only a life of correctness, a life-centered activity but the awakening of enormous energy, radiating and integral to perception, which alone frees man from duality and the bondage of time. It demands muscle and tone and an extension of the horizons of the mind. It is a tough, relentless pursuit, in the ending of which is the arising of insight and the flowering of goodness and compassion.

Pupul Jayakar

(Courtesy from the Krishnamurti Foundation of India )